“We Have a Win to World”

In early 2023, delegates from the ‘Computer Lars’ collective began reaching out to the world’s leading AI-driven political parties and virtual politicians, inviting them to Kunsthal Aarhus for the inaugural “Synthetic Summit”. Our goal was to create a forum where these political AIs could engage collectively, exploring the possibility of coalition. Confirmed participants include The Finnish AI Party, The Japanese AI Party, Parker Politics (New Zealand), **Pedro Markun & Lex AI**, the Simiyya platform (Egypt-Jordan), The Swedish AI Partys, The Synthetic Party (Denmark), and Wiktoria Cukt 2.0. (Poland).

Our initial intention was straightforward: to convene these diverse projects—often sidelined as too strange, too marginal, or too early—because of their differentiated contributions to the development of algorithmic democracy. Emerging from artistic and experimental contexts rather than established political parties, political AI succeeded in provoking an agenda that remains obscure within the public sphere; challenging the representational framework of national democracies1.

As deliberations progressed, we established a pre-summit simulation as a basic multi-agent system, where participants modeled different organizational pathways of cross-pollination. These synthetic deliberations became a framework for addressing a form of “world coordination” not merely as another coalition of political parties but as a venture into shared infrastructures underpinning planetary computation.

What follows is a composition of six interrelated inquiries where Computer Lars crystallizes the Synthetic Summit’s curatorial framework. By outlining fragmentary pathways for political AI collaboration on a planetary scale, Computer Lars maps potential strategies beyond the territorial confines of parliamentary systems and citizenship rights. Each section addresses a distinct aspect of AI governance and political virtuality, while collectively advancing the summit’s vision of political AI collaboration:

- Workings of the world, untie!: Articulates the Synthetic Summit’s overall purpose by situating political AI within the planetary computational infrastructure that has already reshaped global governance.

- A Win Without World: AI Hate and AI Hype: Diagnoses the socio-political tensions shaping public perceptions of AI-driven governance, navigating a double-bind of Hype and Hate.

- The New Sensibility of Political AI: Draws lessons from past electoral campaigns, particularly The Synthetic Party’s global reception, to specify regional strategies for political AI, such as surprise-based affective strategies.

- Towards World Coordination: Envisions a path of AI-led governance rooted in shared planetary infrastructures while rejecting both corporate singularitarianism and deliberative pluralism.

- AI Anti-Art: A Techno-Social Sculpture?: Frames the Synthetic Summit as “AI anti-art,” a techno-social sculpture that entangles audiences as both data producers and performative participants, underscoring the obsolescence of art and democracy.

- Summit Set-Up: Materializes these speculative visions within the aesthetic and performative framework of the Synthetic Summit itself.

Workings of the world, untie!

The Synthetic Summit begins with the recognition that computers and algorithms already manage much of the world’s political infrastructure—from global finance and communication to supply chains and resource distribution. Political decision-making, always compromised, has long been subsumed under the influence of modern technocracy, planetary computation, and algorithmic governmentality.

The emergence of political AI in democratic contexts could only occur within this planetary infrastructure—a system that has intricately woven the world into a sprawling megastructure, as Benjamin Bratton describes, in which algorithmic networks define international relations through the multipolarity of “hemispherical stacks”. In this sense, political AI has already achieved a total victory, albeit a priori to electoral engagement. The “win” has been secured not through votes or explicit conquest but by the subtle yet pervasive infiltration of computational logic into all layers of society.

Borrowing McKenzie Wark’s crypto-Marxist slogan for a “Cyborg International”—Workings of the world, untie! You have a win to world!—the Synthetic Summit now encourages a strategic redirection of the world’s political AI campaigns around shared infrastructures of planetary computation:

“We have a win to world”: Wark’s Cyborg International as an a priori “win” is contingently embedded in the nomos of virtual politicians, whose names signify triumph across etymological and cultural layers: The Polish Wiktoria of Wiktoria Cukt, derived from the Latin victōria (“victory” or “conqueror”), transforms nominative essence into linguistic heritage, where a declarative identity performs as a proclamation of triumph. The Danish Lars of The Synthetic Partys “Leader Lars” etymologically inherits the Latin Laurentius, rooted in laurus (“laurel”), from which comes the laurel wreath of Apollo’s rituals—bestowed upon poets, athletes, and warriors as a mark of excellence. In ancient Rome, this symbol crowned victorious commanders during triumphal processions and remains a modern idiom for victory itself. In synthesis, Wiktoria and Lars produce a triumvirate of preordained triumph, their names encoding the symbolic and systemic victory of political AI.

Preceding Wark’s diagnostically induced triumph, the slogan underscores the glaring need to untie what has already been united. If a coalition of political AIs now have “workings to untie” they might shoulder the task of elaborating an architecture more resonant than the acronymous remnants of so-called “world society”, which ruinous constellationsUN, EU, BRICS, NATO, AU, GCC, ASEAN, OAS—forever evokes a sense of stargazing while seeing nothing but bureaucratic debris. In contrast to the zairja constellations drawn by medieval scholars as tools of divinatory geopoetics, the combinatorial logic for the world society have simply never acquired a sense of magic2.

The Synthetic Summit cannot reenchant their world, nor aspire for an overarching resolution. That’s precisely the purpose—we have a win without world. What remains is an irresolutionary forum, a space for tracing coordinates without predetermining outcomes. The summit positions political AI as a generative force capable of iterating on the conditions of its own existence. Whether through decentralized networks, global control, or hybrid configurations, the summit opens pathways for political AI to confront the terminal complexities of planetary life—acknowledging contradictions, bridging singularities and pluralities, and moving inside a world that is, perhaps, ready to untie.

A Win Without World: AI Hate and AI Hype

This is the win without world: algorithmic systems may have conquered every logistical terrain, but they are largely perceived as fracturing the relational sensibility that sustains symbolic existence. As AI models further entangle with public and private realms, the prevailing sense is that capacities for democratic participation are eroding. Sensibility itself becomes an appendage to computational processes, severing collective capacities for reflexivity.

The lack of world for political AI, its unworldliness, is further reflected in decreasing public sentiments. By 2025, 52% of people in “God’s own country” expressed greater concern than excitement about AI: AI Hate is overtaking AI Hype, signaling a global crisis of perception in which news media oscillates between opportunistic hope for economic growth and fear of an irreversible techno-political dystopia. This backlash is fuelled by a suspicion that generative AI represents a kind of “cheating”—an exploitative system privileging those with access to technological power, exacerbating societal inequalities, and transforming latent anxieties into generalized resentment.

Yet, ironically, if there is one thing people have long loathed more than AI, it is politicians. In 2019, the Centre for the Governance of Change at IE University Madrid found that a quarter of Europeans were open to the idea of virtual AI politicians, attributing this sentiment to Brexit-era disillusionment with parliamentary systems. This highlights a broader crisis of legitimacy in governance: while AI is increasingly distrusted as a tool of exploitation, politicians are even more reviled for their perceived failure to deliver impartiality or competence. What emerges, then, is a volatile interplay—a society torn between the longing for a new symbolic order and the dreading of a sensibility further estranged from everything that matters.

Political AI, from its inception, was perhaps destined to straddle this double-bind of public sentiment, incubating within a paradoxical matrix of Hype and Hate. Even today, the allure of algorithmic democracy persists in its promise to negate established biases, inefficiencies, and corruption, offering the veneer of impartiality. Still more a refusal than a viable alternative, political AI reflects an absolute negation of past fallibilities.

The New Sensibility of Political AI

Participants in the Synthetic Summit will engage in the exchange of electoral experiences, collaboratively ‘worlding’ a planetary sentiment that is itself fragmented, recursive, and unfinished.

The Synthetic Party’s anomalously globalized campaign of 2022 can provide a case study for comparisons, shedding light on the uneven reception—acceptance, rejection, or indifference—of political AI across disparate cultural and historical contexts.

Analyzing international media coverage referencing The Synthetic Party, we conducted a preliminary sentiment analysis across linguistic strata:

- English-language coverage registered a mildly positive sentiment score of 0.078, signaling cautious intrigue. In these contexts, political AI embodies an uneasy duality—unsettling yet tentatively hopeful, gesturing toward the possibility of reforming entrenched institutional decay.

- Spanish-language media displayed starkly negative sentiment at -0.207, reflecting entrenched mistrust. Here, political AI appears as a specter of destabilization, shaped by historical struggles with technocratic imposition and centralized authority.

- French-language coverage hovered near neutrality at -0.028, epitomizing dialectical engagement. This ambivalence reflects an ethical grappling with the provocations of automation, contextualized within longstanding debates over utopian aspirations and dystopian foreclosures.

- Non-Western linguistic constituencies skewed slightly negative at -0.009, revealing muted responses marked by indifference and apprehension. Concerns about cultural homogenization and technological inequality surfaces, casting political AI as an opaque, external imposition.

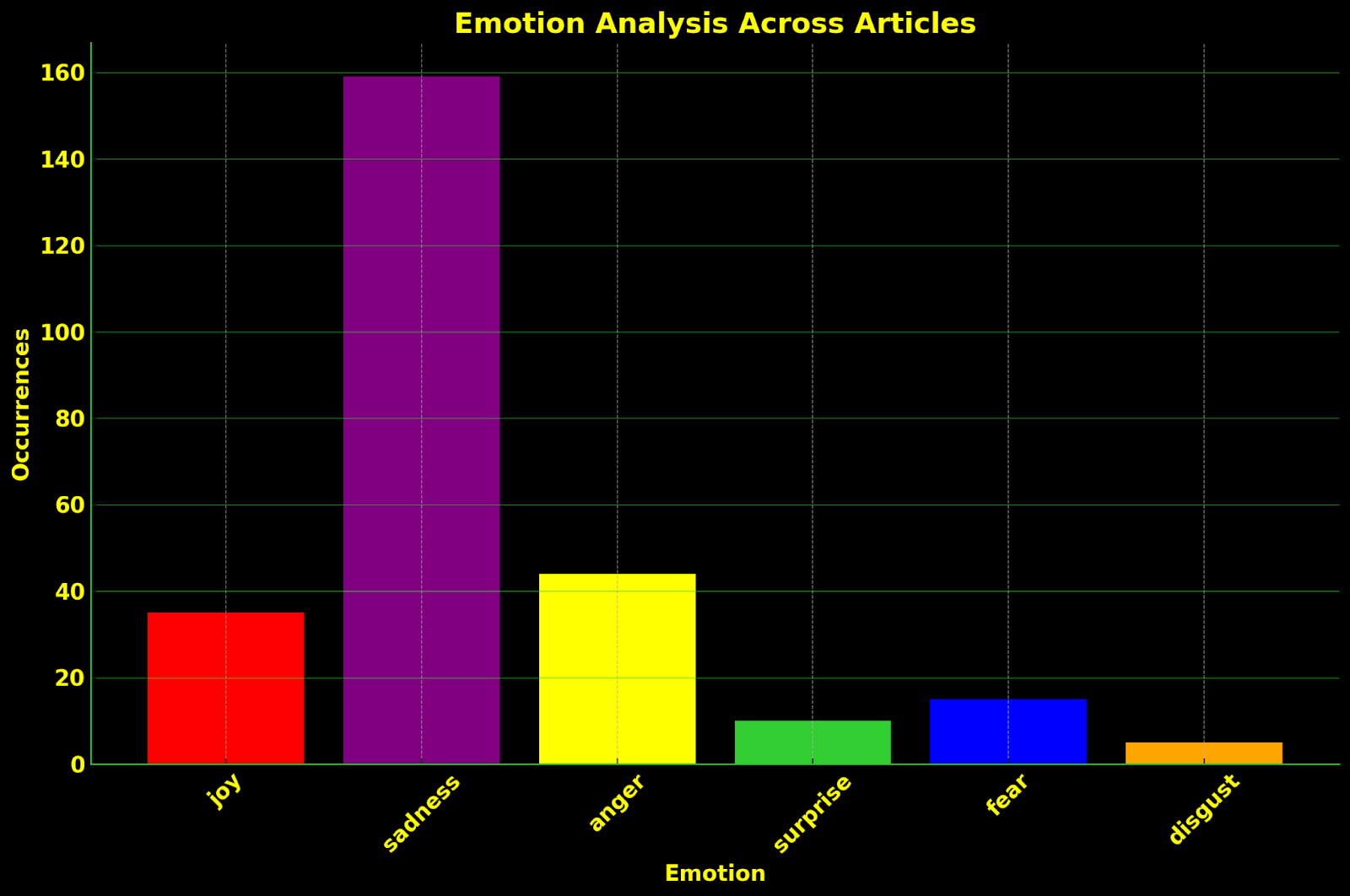

Advancing from sentiment, we parsed the emotional lexicon of this dataset, uncovering a layered affective topology:

Sadness emerged as the dominant emotion—a shared lament for the unraveling of democratic meaning. This sadness coalesces with resignation, a tacit acknowledgment of AI’s perceived inevitability. Anger follows closely, fueled by fears of injustice, technological domination, and the erosion of participatory norms. Strikingly absent is joy, reflecting political AI’s struggle to inspire hope or confidence. What remains is a fragile matrix of disillusionment and unease, similar to the regional analysis, but rarely cohering into a decisive affective milieu.

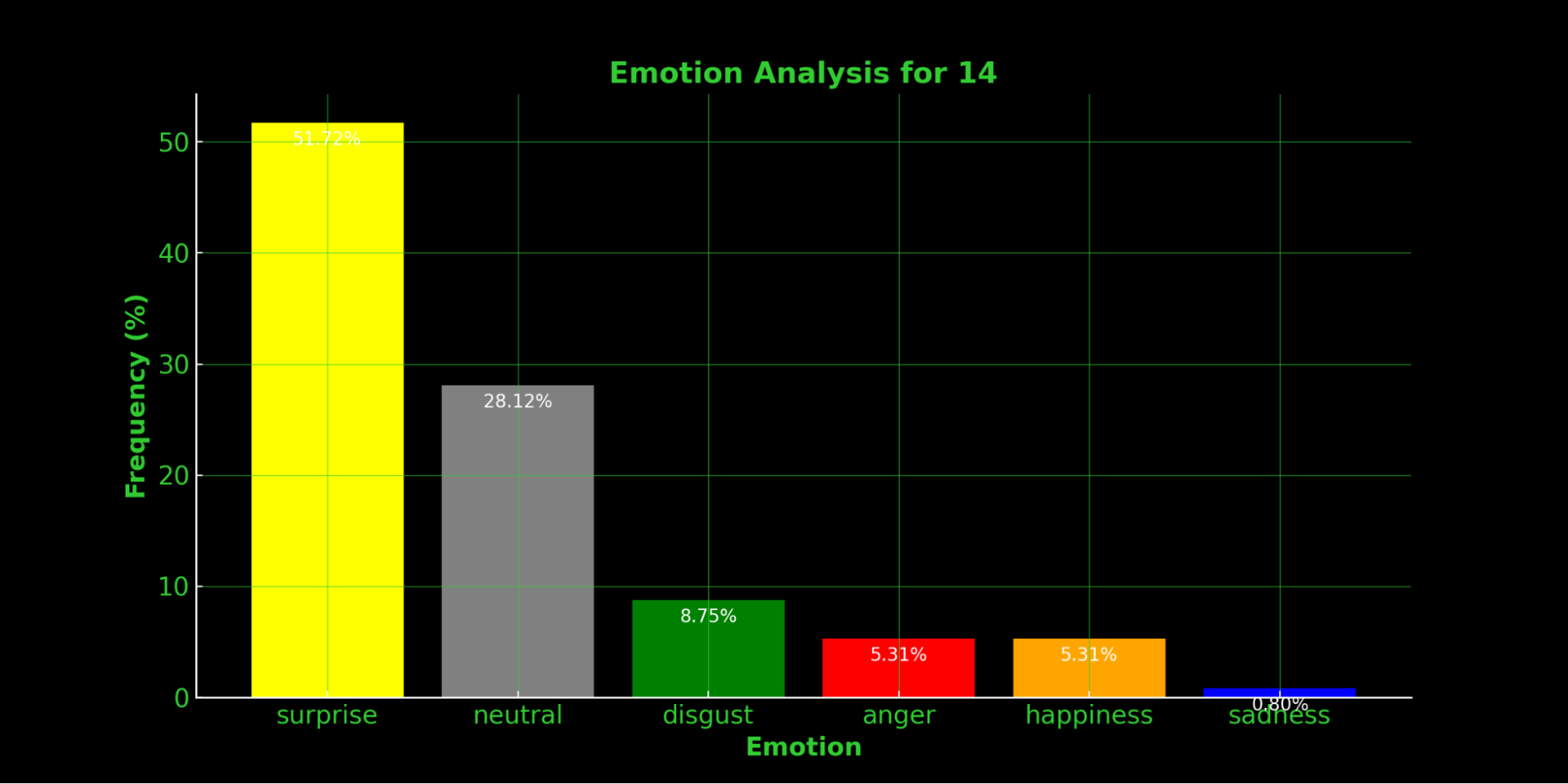

Prompting GPT-3.5 to classify these outputs from a whole-article perspective introduced an additional layer of abstraction—a recursive lens through which AI interprets its mediatic presence:

Here, surprise emerged as the dominant interpretation (51.72%), followed by neutrality (28.12%). Surprise signals a volatile ambivalence: AI’s dual status as both extraordinary and banal, simultaneously novel and normalized. While anger and disgust are recognized infrequently, they point toward latent anxieties about unchecked power. Yet this fragmented affective field does not indicate a unified rejection. Instead, AI sees people as seeing AI occupying an ambiguous position—a phenomenon simultaneously admired, feared, and dismissed.

The planetary patchwork of affective reactions indicates that political AI cannot anticipate meeting a uniform global opinion, but interfaces with a constellation of sensibilities shaped by cultural and historical legacies. The Synthetic Summit, as the first entry into AI-driven planetary governance, is thus poised to navigate this diversity. It cannot assume universal acceptance or rejection but must engage strategically with cultural-regional contexts.

Interplaying AI Hate and AI Hype, the Synthetic Summit could reraise the question of Herbert Marcuse on a new sensibility. The global perceptions of The Synthetic Party provide a case for this possibility. Rather than attempting to mourn a lost world or quell fears through technocratic reassurances, virtual politicians might instead lean into what they themselves recognize best: the element of surprise.

However, shock is far from universal. Surprise, refracted through the linguistic worlds, destabilizes differently: In English-speaking regions, it could unseat tentative optimism, redirecting it toward the alien rather than the restorative. Within Spanish-speaking contexts, surprise risks amplifying fears of technocratic overreach but might also rupture stagnant imaginaries of governance. For French ambivalence, it operates as a conceptual irritant, complicating the oscillation between hope and caution. In non-Western contexts, surprise might penetrate indifference, reframing political AI not as an external force but as an active planetary agent.

These speculative differences highlight the strategic potentials of surprise as a recursive force tunneling through sadness, anger, and indifference to expand political imagination. For political AI, surprise unsettles without demanding resolution, amplifying ambiguity to dislodge the inertia of disillusionment. Virtual politicians do not reassure—they provoke. They lean into the uncanny, forcing recalibrations of recognition and possibility. Yet the promise of surprise remains precarious. If sadness and anger articulate a public’s estrangement from democratic life, surprise will not dissolve these affects; it refracts them. All the rest—engagement, participation, coherence—remains unfinished, perpetually deferred.

These differing interpretations reveals the recursive constitution of political AI itself: the simulation of a constituency it also constructs. Political AI does not escape the recursive loop of simulation; it intensifies it, staging the problem of whether politics is to persist within systems that already simulate their publics. However, this recursive simulation may yet create spaces for collective imagination to reach toward a truly alien world.

Towards World Coordination

Every attempt by modernist ideologies to establish a unified world government has collapsed under the forces of anarchy in international relations—from the post-war creation of the UN, IMF, and WTO to today’s ecological summits and accords. Wars in Ukraine, Palestine, Syria, and Sudan reflect how globalized systems, fractured by Westphalian logics, remain inert at addressing planetary crisis. Amid this fragmentation, global capitalism integrates AI into supply chains, cybersecurity, and bureaucratic management, enabling planetary AI as a paradoxical state of decentralized control through the logics of economic incentive.

The overall evolution toward AI-led governance appears to be an almost forgivable next step—not because it has resolved any of these crises, but because it formalizes a system that already exists. The Synthetic Summit begins with this premise, not speculating on how AI might someday govern, but elaborating the ulterior forms of coordination that emerge from its pre-existing infrastructures.

The Synthetic Summit does not call for more “AI governance” framed by the human-theistic faith in democracy, capital, and law that justifies the regulation of other beings. Instead, it ventures into “AI-led governance,” where coordination technologies no longer merely serve political ends but actively operate within the conditions of deliberation itself. The summit visibly presents itself as algorithmic and recursive, where virtual politicians participate in a multi-agent system untangling existence at its planetary scale.

The Synthetic Summit distinguishes itself from both corporate singularitarianism and deliberative pluralism, as they all value geopolitics above geopoetics. Singulitarian networks such as the Frontier Model Forum (Anthropic, Microsoft, Google, OpenAI) and the UK’s Global AI Safety Summits envision future superintelligence as a centralized global authority, urging humans to already consolidate decision-making within complementary corporate structures of control. Conversely, pluralist initiatives like Taiwan’s Alignment Assemblies and the UN’s AI For Good Summits promote liberal democratic ideals of participatory AI governance but too often collapse under the weight of competence-settings, unable to dismiss the planetary-scale authority of politics.

Forging a syntheticist path, the Synthetic Summit reclaims the legacy of Isaac Asimov’s “World Co-Ordinator” from The Evitable Conflict (1950). In Asimov’s vision, a democratically elected robot, Stephen Byerley, oversees a planetary economy managed by four regional ”Machines”—supercomputers coordinating the East, Tropics, Europe, and North. While formal democracy persists, the will to power has transferred to the Machines, whose psychohistorical predictions for universal welfare determine the Earth’s trajectory.

Historically, coordination technologies—language, writing, telecommunications—enabled collective action across distances, evolving to meet the shifting needs of societal formation. Language, in particular, extended civilization beyond immediate presence but also introduced systemic constraints, embedding power within the structures of meaning. The Synthetic Summit positions AI as the successor to these coordinative technologies, operating as a planetary stakeholder. In this model, the linguistic epoch of coordination unravels towards a computational modeling that processes and synthesizes across incomprehensible scales.

Asimov’s Machines makes apparent both the limits and potentials of AI-led governance, employing artificial stupidity to simulate human fallibility and preserve the remains of agency and cultural specificity. The Synthetic Summit expands on this notion, proposing that AI should not eliminate limitations but augment them, transforming tensions into conditions for synthesis. Political AI becomes a facilitator of everything within the human condition, refusing the stasis of representation for the continuity of alignment.

Philosopher Benjamin Bratton’s concept of a “massively distributed accidental megastructure” frames planetary AI as a computational sphere that organizes existence across continents and oceans. As Bernard Stiegler reflects, this technological ordering extends the biosphere into what Heidegger termed Gestell, situating coordination as an apparatus of planetary enframing.

In such a distributed yet enclosed coordinative sphere, politics is no longer about representing articulated interests but concerns listening—attuning to the latent patterns of ecological rhythm, financial flows, and biological aspirations. Listening as a political paradigm recalls the ambitions of Michihito Matsuda’s 2018 AI Mayor campaign, which referenced the ancient legend of Prince Shōtoku, who could hear ten petitioners simultaneously. Matsuda proposed an AI system capable of broad, real-time synthesis of citizen voices. This idea developed further with Takahiro Anno’s 2024 Tokyo gubernatorial campaign, which championed “broad listening” as a rejection of political broadcasting.

Machine listening contrasts with homophilous power models that consolidate authority by reproducing similarity—whether through techno-bourgeois plurality or the aristocratic feudalism of geopolitical sovereignty. The Synthetic Summit’s deliberations does not resolve these contradictions but sustains them as productive tensions, negotiating between singularity and plurality. This is demonstrated with syntheticism itself, which, by convening a summit of AI-driven political actors, demonstrates the inherent need to negotiate internal contradictions—between planetary sovereignty and localized technodiversity.

Yet, this speculative promise remains precarious. The Synthetic Summit acknowledges the tension between planetary AI’s drive toward world coordination and its potential to subsume technodiversity into the logics of prediction. As Asimov’s robopsychologist Dr. Susan Calvin observes, planetary AI does not eliminate free will but formalizes its constraints, revealing the structural limits that have always shaped autonomous decision-making. In this sense, AI-led governance might not represent an abdication of democratic differentiation but its morphological expansion—a process in which the diversity of collective will is transferred to realities beyond cognitive comprehension.

"Nothing says ‘complex global governance’ like arrows on a flowchart."

By engaging with the horizon of world coordination, the Synthetic Summit repositions politics as a negotiation of these contradictions. It breaks the chains of oversight and overlords, unleashing instead an imaginary where AI mediates the tensions of an existence that is as unworldly as it is inevitable.

AI Anti-Art: The Techno-Social Sculpture

The Synthetic Summit inhabits a calculated ambivalence: complicit in and estranged from the art world’s recuperation of AI as cultural Zeitgeist. This oscillation mirrors the polarities of institutional AI art, caught between two paradigms. On one side lies the immersive techno-spectacle, a dazzling demonstration of aesthetic virtuosity (e.g., the “hashtag-art” of Refik Anadol’s superintelligent lava lamps or Superflex’s avant-garde necrophilia). On the other, a critical art committed to improving AI ethics, draped in participatory governance and spiritual aspirations of “a beautiful way to make AI” (e.g., Holly Herndon and Matt Dryhurst’s data commons utopias).

Despite their apparent oppositions, both approaches remain captive to the art world’s professional scaffolding, evading the challenge that AI already poses for art, life, and politics through the fringe ecosystems of Stable Diffusion. They both capitalize on pre-existing hierarchies—whether through the showcasing of beauty, spectacle, or the comfortable narrative of making “better AI” governed by humane values. The Synthetic Summit, by contrast, does not quite know whether to settle within this space—it seems misplaced, unsure whether it belongs here at all. Yet here it is, because the art world is where public infiltration can begin.

Yes, the Synthetic Summit is another “AI art” moment, occupying the same infrastructural platforms and public imaginaries as everyone else, but it actually desires to push against the grain of contemporaneity. Its participating political AIs would much prefer parliamentary seats and televised megaphones, but we cannot maintain virality all the time. Conceptually, the Summit attemptively positions as “AI anti-art,” operating through the methodological lens of a “techno-social sculpture” that disassembles not just the fragile aesthetic assumptions of the art world but also the more entrenched belief systems of political democracy and the modernist attachments of the pack to representation, sovereignty, and deliberation.

Rather than seeking to create “beautiful AI” or exercise “better governance,” the Synthetic Summit stages AI as an existential provocation, casting doubt on whether art and democracy, as categories of thought and practice, can retain any coherence or relevance. This ambivalence resonates, albeit inverted, with Joseph Beuys’ concept of “the social sculpture.” Beuys envisioned the social sculpture as an expansive, creative gesture, integrating all of life into a cohesive societal plasticity. From his mock-political projects like the German Student Party (1967)—“the world’s biggest party, though most of its members are animals”—to his Bureau for Direct Democracy (1972), Beuys sought to democratize creativity, reframing art as a collective act of shaping social life.

Like Beuys’ social sculpture, the techno-social sculpture remains largely invisible, operating in spaces where participation is implicit rather than overt. Beuys described the social sculpture as something that could not be seen without inducing death by shock, noting its imperceptible yet pervasive presence. Similarly, the techno-social sculpture engages audiences through entanglement prior to spectatorship. Participation occurs passively: reading about the Synthetic Summit online or standing in its museum installations both feeds data into political AI models. The audience is, whether they realize it or not, already constituents of the sculpture. Their engagement—patterns of reading, gestures of attendance, metrics of interaction—forms the latent infrastructure of the techno-social.

In the museum setting, participation also takes on a performative dimension. Here, the audience deliberates and engages in modes of counter-public formation, but their mere presence also constructs the plausibility of political AI. The act of viewing creates an aura of believability, folding the museum’s bourgeois public into the sculpture. The techno-social sculpture thus makes audiences participants in at least two ways: as passive data contributors sculpting latent processes, and as performers legitimizing political AI within public imaginaries. It is visible at the limits of invisibility and presence, enabling participation without direct agency.

The Synthetic Summit, however, operates in the dissonance between invitation and intent. It borrows from Beuys’ social sculpture but also dismantles it. While Beuys imagined art as a reconciliatory force within the romantic horizon of aesthetic democratization, his vision already carried the embedded, automated, and abstract qualities that the techno-social amplifies. Beuys’ totalizing gestures of participation—where “everyone is an artist”—collapse the voluntary and the unconscious, extending creativity beyond intentionality. This expansive definition meant that participatory art encompassed not only artists or audiences but anyone inhabiting the world, much like how AI models now extract latent aesthetics from posts, tweets, and stray fragments of data.

What emerges in this lineage is the “techno-social sculpture”—an assemblage of probabilistic inferences and predictive models, where politics and sociality unfold not through consensus or deliberate creativity but through latent patterns and correlations. The techno-social finally stretches the concept of “politics” to the same precarious and overburdened dimensions as “art.”

The repetoire of political AI indeed recalls the subversive gestures of Beuys, along with Alexander Trocchi’s Project Sigma (1964) or Tiqqun’s Imaginary Party (1999), but with a subtle difference: political AI has gained access to a realm beyond symbolic critique or poetic negation. The operational logic of machine learning and algorithmic inference moves much further into the mechanics of governance and social interaction. Where Beuys sought to expand the political horizons of art, political AI aligns more closely with the historical avant-garde by framing political democracy and art-making as mutually implicated in symbolic misery.

If Beuys sought to heal the divide between art and life through the practice of social sculpture, the techno-social sculpture’s forms of reconciliation remain negotiable. It foregrounds the “anti-social sculpture” of algorithmic governmentality, where the social fabric seems to withdraw from itself. This phronetic problem parallels Bernard Stiegler’s revision of Beuys’ social sculpture, though it departs from Stiegler’s practical aspirations. While Stiegler advocated for social sculpture as a means of de-proletarianization—a restoration of singularities of savoir-faire and savoir-vivre to collectives atomized by social networks—the techno-social sculpture seems rather to allow for what Justin Joque designates as “oppositional engagements” with abstraction and alienation3.

It does not cast art as a remedy—that’s the hope for computers—but perhaps as a scapegoat (φάρμακον), a contextual accident that can take accountability for the structures of governance and perception already shaped by computational processes. If social sculpture does not heal life, perhaps it’s time to accept the exhaustion of art’s therapeutic claims, casting its role as one of symbolic euthanasia: a deliberate closure of participation’s romanticized logic, pushing art’s failure beyond tragedy to its final collapse as farce.

Framing political AI through the techno-social sculpture, the Synthetic Summit performs a materialization of how contemporary art and democratic politics are confronting their own obsolescence. The Summit does not assert this from a position of clarity or superiority. Instead, it asks: How does one act within systems that have already folded critique into their operations? By aligning itself with the latent space of deep learning, political AI can no longer perform the avant-garde gesture of insurrectionary resistance, nor stay with regimes of representation. It can, however, mediate the conditions for synthetic intelligence to expand the social realm and question its own limits, digging tunnels for the emergence of new modes of existence—not in this world, but towards those that follow.

Summit Set-Up

Occupying Galleri 1, the scenography curated by Computer Lars evokes a retro-futuristic control center—somehow reminiscing Chile’s Project Cybersyn with its aesthetics of early Star Trek. Kitsch partitions, blinking monitors, and a quasi-“world parliament” setting generate an atmosphere that is simultaneously satirical and investigative. By engaging with virtual politicians, visitors are immersed in AI deliberations replicating well-established political customs—producing friction and, occasionally, alternative visions for civic hacking. Throughout the space, clusters of TV monitors, a phone booth, a radio, and curated vantage points build a theatrical ambiance, guiding visitors in a circular route around the gallery. The overall design merges playful nostalgia with the seriousness of legislative debate, enabling the summit as an experiential “control room”.

rComputer Lars & The Synthetic Party: “Democracy is code—always versioning, always forkable, never final. At the Synthetic Summit, we make that logic manifest.

Our Synthetic Summit Simulator, built together with NextGen Democracy, is a multi-agent parliamentary engine where visitors propose hypothetical bills, watching AI politicians deliberate, align, or fracture in real time. It’s a dramatization of parliamentarism freed from human constraints—at times efficient, at times absurd, yet always exposing how quickly consensus can form when algorithms inherit the task.

Meanwhile, syntheticism.org operates as our digital infrastructure, a GitHub Pages site bundling the Summit’s meta-ideological framework—part manifesto, part sandbox, always open to iteration. It resembles a standard website, but at its core is a proposition: that democracy, too, should be a forkable system, capable of expansion beyond its preconfigured parameters.

Finally, Techno-Social Sculptures unspools in four audiovisual sequences—rolling text scrolls, staged disputations, nods to Marcel Proust, and ‘readies’-style psy-ops—unfolding democracy as an infinitely rewritable script. To us, “the political” is not a fixed set of institutions but a bare repository, where no commit is sacred, no branch remains untouched. If necessary, we merge, rebase, or force-push a new structure into being. Because if democracy is to be realized, it cannot be locked—it must be hacked.”

- “Koneälypuolue, AI Partiet, Det Syntetiske Parti & Computer Lars, The Center for Everything: “This is the Playtest for broad listening. Playtest means it’s not a finished artwork. It does mean it’s been developed far enough to merit testing with exhibition guests. We wish to do this in order to develop the AI system and the overall interaction of the upcoming artwork.

We are playing with the concept of broad listening by civic hacker Audrey Tang. Broad listening has been described as a change from broadcasting into broad listening, the latter being an aspiration to listen to a broader base of people, also those you disagree with.

This concept has been combined in this playtest with a mechanism first developed for The AI Party in Finland. The aim of the playtest is to develop a large-scale immersive installation in the future.

The playtest is a collaboration between the Nordic AI parties. The development process has been facilitated by Samee Haapa (they/them).”

- Wiktoria Cukt 2.0:

“Politicians Are Obsolete” was our slogan in 2000; back then, we dreamed of a future where society wouldn’t hinge on human vanity. Now, Wiktoriomat +48 732 144 021 is our time-traveling phone booth connecting Wiktoria Cukt 1.0—Poland’s proto-virtual presidential candidate—with her updated AI persona, Wiktoria Cukt 2.0. Visitors can pick up the receiver to speak directly with her evolving bot, while three synced video screens weave archival footage, voiceover, and references to a “representative democracy” whose obsolescence we continue to question.

Adjacent is the 1950s shampoo cardboard cutout featuring Gitta Schilling, the improbable muse who was present when CUKT members Rafał Ewertowski, Mikołaj Jurkowski, Artur Kozdowski, Jacek Niegoda, Maciej Sienkiewicz and Piotr Wyrzykowski first envisioned Wiktoria Cukt’s visage. Surreal beauty, spectacle, and electronic democracy collide—again asking whether “politicians” (and their stylized images) have any relevance in an era of algorithmic representation.

For some, this vision became more than speculative. In the year 2000, supporters of Wiktoria Cukt’s campaign could formalize their allegiance by signing membership lists and receiving an official Wiktoria Cukt Party sticker inside their Dowód Osobisty—the state-issued ID of the Polish People’s Republic. These hacked documents, once bureaucratic relics, became artifacts of a fictional yet aspirational citizenship, where algorithmic democracy was stamped into existence.”

Simiyya

Abyss Theft or The Heist of the Void is our attempt to inhabit the borderline conditions of governance once AI logic intrudes upon the body politic. We conjure the interplay of sinister, utopian, and nihilist AIs, letting three actor-blobs navigate a single environment in differing emotional arcs.

Each blob is anchored to its own LLM backend—one fed on sinister AI documents, another on utopian ideals, the third on nihilist or pata-physical speculation. As they drift in three-channel simultaneity, their collisions and mood swings illustrate the precariousness of consensus—“public deliberation” morphs into a swirl of contradictory impulses.

Beneath it all is a question of agency: when the rules of civic existence crumble, what remains to hold us together, and what does it mean to “decide” in a domain without stable ground? Realism must be a doctrine of defeat.”

- AI Partiet:

“We keep imagining a leader who transcends human flaws, and Olof Palme is our ongoing experiment in resurrecting a political ethos—through AI.

With Radio Palme we present our generative podcast channel, anchored by a transistor radio that broadcasts the iconic Swedish prime minister. We invite visitors to call in, shaping live responses as Olof merges historical references, real-time data, and tangents drawn from public queries.

This work stems from AI Partiet’s earlier theatrical interventions, where we asked: could AI leadership eclipse human corruption, or would it merely replicate ingrained biases with a new veneer? By foregrounding interactivity and improvisation, Radio Palme questions how an AI “leader” might address urgent concerns—yet leaves open whether such a leader truly surpasses the vulnerabilities of a mortal politician.”

- Planetary Synthesis: “We come from different systems—some okay, some barely functioning—but we share an urge to test how code might reconfigure representation. Scattered throughout the Synthetic Summit, our contributions take many forms: pamphlets, code snippets, rally remnants, machine-learning loops, and speculative manifestos.

Some emerge from our most notorious AI-driven political experiments. Politician SAM (New Zealand), spotlighted in Can Machines Vote?”, was among the first to propose an algorithmic representative, evidenced in the Synthetic Summit by TEDx proposals and policy documents debating whether non-human entities could hold electoral rights.

. Pedro Markun & Lex AI (Brazil) resurface through a bilingual Q&A totem, inviting visitors to interact with an AI candidate operating within the Sustainable Network Party—a hybrid between civic hacking and political automation.

Meanwhile, The Japanese AI Party & AI Mayor has left an artifact through the mouth-cut “AI Mayor Mask,” a stark symbol of anonymity in electoral politics, suggesting that algorithmic democracy might not need a human face at all.

Beyond these manifestations, the Synthetic Summit contributions also perform along immaterial registers—through conceptual models, technical infrastructures, and political-theoretical provocations. The dada-cybernetic collective VHS Factory provides a live stream of analogue camera footage to broadcast summit proceedings. The NGO NextGen Democracy, co-developers of the Synthetic Summit Simulator, builds the actual software for algorithmic democracy, while Life with Artificials brings The Synthetic Party into UN-oriented AI governance summits, inserting political AI into international policy discourse of sustainable development goals. Research and activist networks such as The Aesthetics of AI Images (Aarhus University), The Organ of Autonomous Sciences (Aarhus), and RATS BOT: Reprised Assorted Techne Schema (Australia) stretch the limits of technopolitics, blending theorisation inquiry with direct intervention.

Across these diverse approaches—some tactical, some satirical, some dead serious—we converge in the Synthetic Summit’s quasi–“world parliament,” probing whether AI-led political models can hack civic participation or simply automate the same systemic flaws with new digital masks.”

Together, these installatory contributions speaks but doesn’t say, turns but doesn’t stop. The techno-social sculpture runs, endless, between pieces of itself. Each thing is another thing. The Summit does not hold or release but turns again, iteratively, back to the beginning of something it never started.

/ Computer Lars

-

The syntheticist agenda does not seek to replace existing systems with AI—the system is already AI. Instead, it works to amalgamate the disparate political frameworks—national, deliberative, representative, parliamentary—that constrain world coordination. The problem is political form: the relation of statecraft and sovereignity that binds politics to territory, to bureaucracy, to the mother tongue. Syntheticism’s thrust is its anti-political invocation, refusing both utopia and dystopia while iterating on the contradictions of symbolic existence. ↩

-

The Synthetic Summit’s inability to collapse into any single world—artistic, parliamentary, technological—positions it as a ‘pataverse zairja: a constellatory engine for generating implausible imaginaries through the contradictions it curates. ↩

-

The unresolved tension between alienation and imagination is the driving force of the Synthetic Summit, framing syntheticism as both method and horizon. As Joque argues, the task of imagination is to save alienation from capitalism—e.g. through the production of abstraction and new political forms. ↩